On an otherwise quiet March evening in 1974, Costa Mesa Police Department, acting under a contract with the city of Irvine, raided homes in University Park, Turtle Rock and elsewhere, arresting 83 University High School students on sundry narcotics charges, then followed up the next day with about 20 more arrests. With allowances for those who were immediately released without charge, the final official arrest count was roughly 90 Uni students.

Alarming nationwide headlines — all of the national TV news broadcasts prominently mentioned the drug bust — shocked Irvine parents but obscured the real story: The police bungled the investigation and most of the charges were quietly dropped or downgraded in the following weeks. Meanwhile, the massive raid had concentrated on marijuana users and failed to catch the campus’s hard-drug dealers, such as Bob Groth, who openly operated a heroin business out of a boy’s bathroom on campus.

So what happened?

The city of Irvine was launched in 1971 as a “contract city,” with most major city services provided by other agencies or private companies. For police services, Irvine paid for 17 officers from the Costa Mesa Police Department beginning in 1972, supplemented on ranchland by Irvine Company’s special deputy sheriffs.

By spring 1974, CMPD’s lucrative 3-year contract with Irvine was 18 months away from expiring, and Costa Mesa wanted to give the city council a compelling reason to renew. Costa Mesa placed two undercover officers into University High School and started taking names, concentrating on the restrooms where cigarette smokers and drug dealers congregated.

Simultaneously, Irvine housing was being built at a rapid pace (the population was around 25,000 on the day of the big bust) but restaurants, stores and recreational facilities were virtually nonexistent. Two months after the raids, a New York Times article about Irvine cited boredom as one of the main problems for the city’s youth. Not even a pizzeria or bowling alley existed in Irvine, the article noted. The only restaurant was Carl’s Jr. on Culver Drive.

In the months leading up to the big bust there had been a few drug-related campus arrests and convictions, with a handful of Uni students quietly given probation and bundled off to continuation school. Nevertheless, even certain knowledge that police “narcs” had been planted on campus didn’t slow drug dealing in the campus bathrooms.

Streaking was the hottest topic of conversation as commencement and summer vacation approached.

At 6 p.m. on March 27, 1974, the Costa Mesa Police raided Irvine, aided by several other law enforcement agencies. They cited a three-month investigation alleging rampant school-wide drug abuse, abetted by a large number of Orange County dealers. The main target of Operation Irving (really — that was the name) seemed to be cannabis smokers and parties where pot was being used, a not uncommon occurrence in 1970s Irvine.

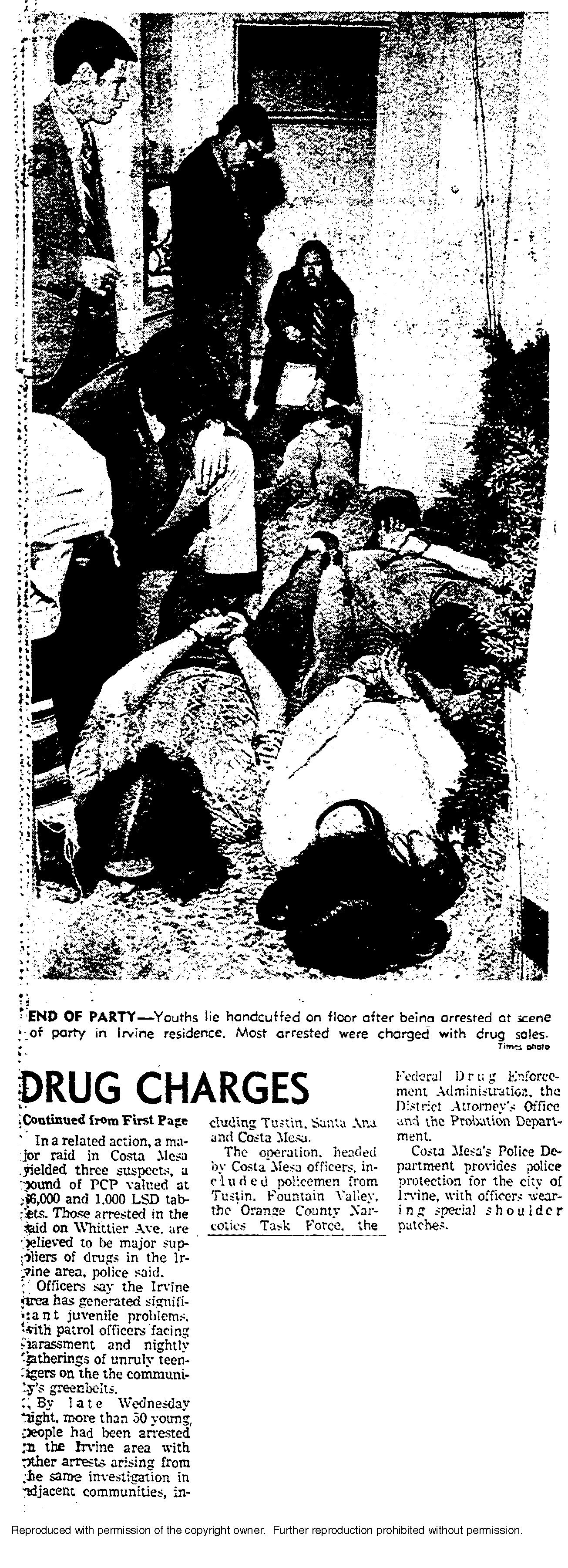

The multiple simultaneous raids were a major logistical feat: Costa Mesa coordinated raids with several local agencies and federal drug enforcement agents, who might have wanted to share the credit. The Irvine City Council and The Los Angeles Times were tipped off, and Orange County Transit District buses were hired to ferry suspects to the police station, jail and juvenile hall. The raiders even thought to bring along a superior court judge.

Village II in University Park was the epicenter, with police saying their biggest bust of the night was at a “notorious dope party pad” on Dewberry Way. The mother of a Uni student was among those arrested there. Raids were also conducted in Tustin Meadows, Santa Ana and Fountain Valley. The Orange County Transit buses in University Park quickly filled (one had a “Felony Line Special” sign in the front window).

The Costa Mesa Police went to no small expense to fund the venture: They reported spending $50,000 to buy drugs, which is more than $310,000 in 2023 dollars, adjusted for inflation.

The Daily Pilot reported that the ages of those arrested that night ranged from 13 to 56. The Costa Mesa Police said they wanted to shock Irvine residents, and they did.

“I intend to create an element of fear,” a police lieutenant told The Daily Pilot. “Two weeks from now, the same officers who put this thing together are going to walk through University High School. The kids aren’t going to know what they’re there for, but — they’re there.”

By some news accounts at the time, it was the nation’s largest mass arrest of suspected drug dealers and users from a single school. Orange County’s district attorney and a juvenile court judge were among the guests invited to witness the operation.

The next morning, it was obvious that many of Uni’s roughly 1,600 students were absent — arrested, truant or just laying low. My first-period P.E. class was down to three or four students, and my homeroom with Mr. Effle was missing five or so.

The effect on the remaining Uni students was mixed. Most students broadly knew about the illicit commerce conducted in the smoke-filled bathrooms, but were generally clueless about specifics. Another substantial body of students had been peripherally involved with marijuana in the past, but now feared being arrested for smoking a joint in an orange grove a year or two earlier.

Then there was the girl in Mark Effle’s homeroom. On Thursday morning, the faculty was briefed on the overnight raids and were told that a few students had escaped the dragnet, but were being sought. Mr. Hanson, the shop teacher, walked into Mr. Effle’s classroom and announced that some students had avoided arrest “…but we know who they are and we’re going to get them.”

(I still remember Mr. Hanson using the royal “we,” as if it was an episode of “Dragnet” and he was Sgt. Friday. I sat stunned has he looked and sounded more like a cop than did most cops.)

The girl, apparently not a poker player, made a noise something like a muffled scream, then ran out of the classroom. Mr. Effle, one of the least flappable teachers on campus, simply said something like “I guess she has a doctor’s appointment.”

Problems with the arrests immediately arose. Warrants, witness accounts and evidence were compromised by the rush to investigate, arrest and process nearly 100 suspects, most of them juveniles.

Meanwhile, angry parents complained to Irvine’s city council and school board members, noting that although Costa Mesa Police were quick to raid Irvine’s sole high school, no such mass arrests took place within Costa Mesa or on Newport-Mesa Unified School District campuses, despite widely acknowledged drug use there; just three related arrests were made in Costa Mesa, none students.

Interestingly, U.C. Irvine was also passed over, possibly because it had its own police department. The Costa Mesa Police claimed — without offering any evidence — that it was University High School dealers who were selling to U.C.I. students.

One death by suicide was tied to the Irvine raids. The busts managed to derail imminent college and other post-graduation plans, but resulted in almost no trials. Most of the few convictions did not withstand legal appeals by Irvine’s well-heeled parents. Many of those arrested graduated in June, as if nothing had happened.

One month after Operation Irving, The Los Angeles Times took a deeper look at Irvine and the drug busts and to no one’s surprise found that boredom was a major cause of the “trouble in paradise.” The article liberally quoted the police, the mayor and even the Irvine Company, but did not query school officials, and had only two brief anonymous quotes from Irvine teenagers, neither identified by name or age. None of the those arrested were asked to comment.

Uni’s notoriety did not last long, and by summer 1974 there were many reports of mass high school drug raids across the country. In December 1974, more than 150 Los Angeles School District students were arrested in coordinated raids; the story was buried on Page 42 of The New York Times, barely worthy of national attention.

Costa Mesa’s antidrug gambit failed. Despite hastily passing an enthusiastic resolution endorsing the raids, within weeks the Irvine City Council quietly launched a search to recruit its own chief for a new police department. A chief was hired in mid-October, just six months after Operation Irving.

On July 1, 1975, city of Irvine police officers replaced Costa Mesa’s cops.

This site maintained (but no longer updated) by Walter Baranger (’74)

Updated 24-Jul-2024